THE BEGINNING

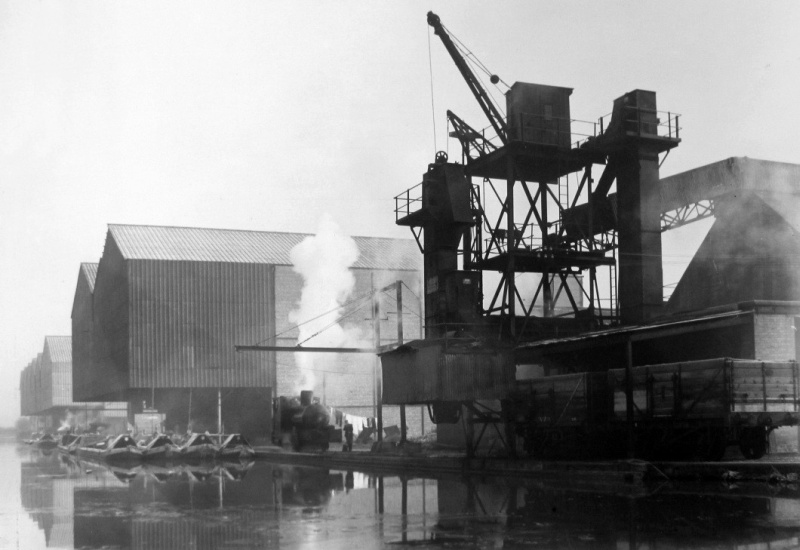

In the 17th century, as early industry started to expand through the growth of the Industrial Revolution, the country’s transport system was clearly inadequate. Huge amounts of raw materials and heavy produce needed to be transported along mostly un-surfaced mud roads by horses and carts or by coastal shipping. A small amount of goods were carried along navigable rivers. Coastal shipping and river transport had obvious restrictions particularly the latter as they did not always run in the right place. Horses and carts could only carry a few tons of cargo at a time, and this became impossible after periods of heavy rain when the roads became impassable.

The factories of the industrial revolution required large quantities of coal and iron ore and transport of small tonnages meant prices were high and placed a severe restriction on expansion and economic growth. A horse-drawn canal boat could carry thirty tons at a time, much faster than on road and at a fraction of the cost.

The first canal is usually associated with Francis Egerton, 6th Earl and 3rd Duke of Bridgewater. As a young man he had taken the Grand Tour of Europe and had been greatly impressed by the continental canals. As a colliery owner in Lancashire it was this experience that spurred him on to develop this form of transport to move coal from his collieries to the industries that needed it.

The Duke presented his first Bill to Parliament, which was supported by the traders of Manchester and Salford on the Duke’s promise that he would reduce the delivered price of coal in Manchester. The Duke’s Bill received Royal Assent on 23rd March 1759. At this time James Brindley, a reputable mining engineer, was surveying the route of a proposed canal from the Trent to the Mersey for the Duke’s brother-in-law. Brindley was invited to a meeting and a plan emerged that would include a stone aqueduct to cross the river Irwell therefore joining Trafford Park to Streford and Manchester. A change to the Bill was presented to Parliament for approval to a change to the canal route and this was passed in March 1760. This renowned engineering feat crowned the success of the opening of the canal on 17th July 1761. The canal was completed through to Streford and to Castle field Wharf, Manchester by 1765.

Affectionately known as the “Duke’s Cut” the Bridgewater Canal revolutionised transport in this country and marked the beginning of the golden age of canals which followed from 1760 to 1830.

CONSTRUCTION

For every new canal, an Act of Parliament was necessary to authorise construction. As people saw the high incomes achieved from canal tolls, canal proposals were put forward by investors interested in profit from dividends, at least as much by businesses which would profit from cheaper transport of raw materials and finished goods. During this period of canal mania, huge sums were invested in canal construction and the canal system rapidly expanded to nearly 4000 miles in length.

Brindley designed and built nearly 400 miles of canals. His biggest, the Trent and Mersey Canal linked two major industrial areas of Britain.

Canals had to be waterproofed and Brindley used an old process known as “puddling” which was a process of mixing clay with water and lining the sides and bottom of the canal. Canals also need to run on the level so hills posed problems. Brindley tried to go round hills where possible but when this was not achievable he used a system of locks to move the canal boat up or down to a new level.

For reasons of economy and the constraints of 18th century construction technology, the early canals were built with a narrow width lock. Brindley set the narrow canal lock dimensions on the Trent and Mersey Canal in 1776 at 72 feet 7 inches (22.1m) long by 7 feet 6 inches (2.3m) wide. The narrow width was perhaps due to the fact that he could only build the Harecastle Tunnel to accommodate

7 feet (2.1 m) wide boats. He built wider locks at 72 feet 7 inches (22.1 m) by 15 feet (4.6 m) wide when he extended the Bridgewater canal to Runcorn.

The Trent and Mersey narrow locks limited the size of boats which came to be called “narrowboats” which is what we know them as today. These boats could carry about thirty tons of cargo. This decision had long term effects in making the canals uncompetitive for freight transport and by the mid-20th century it was not possible to work a thirty ton load economically.

GEOGRAPHY

Brindley’s vision was to use the canals to link the four great rivers of England: the Mersey, Trent, Severn and Thames. The Trent and Mersey Canal was the first part of the network, but he did not live to see it completed. In January 1790 coal was finally transported from the Midlands to the Thames at Oxford, 18 years after his death. Development of the network was carried out by other engineers such as Thomas Telford whose Ellesmere Canal helped link the Severn and the Mersey.

The bulk of the canal system was constructed in the Midlands and the north of England where heavy cargoes of manufactured goods, raw materials or coal most needed carrying.

Whilst most of the canal traffic was internal, the network linked with coastal ports such as London, Liverpool and Bristol allowing cargo exchange with seagoing ships for import and export.

The great manufacturing centres of Manchester and Birmingham were major economic drivers of the canal mania which was at its peak by 1793, and most of their canal networks exist today.

Birmingham and the Black Country had about 160 miles of canals which were dubbed the Birmingham Canal Navigation (BCN) and constructed to serve the manufacturing industries. Similarly Greater Manchester had a dense network of canals serving the local textile industries.

OWNERSHIP

On the majority of canals the canal-owning companies did not own or run a fleet of boats, since this was usually prohibited by the Acts of Parliament setting them up to prevent monopolies developing. Instead they charged private operators tolls to use the canal. These tolls were also usually regulated by Acts. These tolls were used, with varying degrees of success, to maintain the canal, pay back loans and pay dividends to their shareholders.

The canals usually froze in winter and special icebreaker boats with reinforced hulls would be used to break the ice.

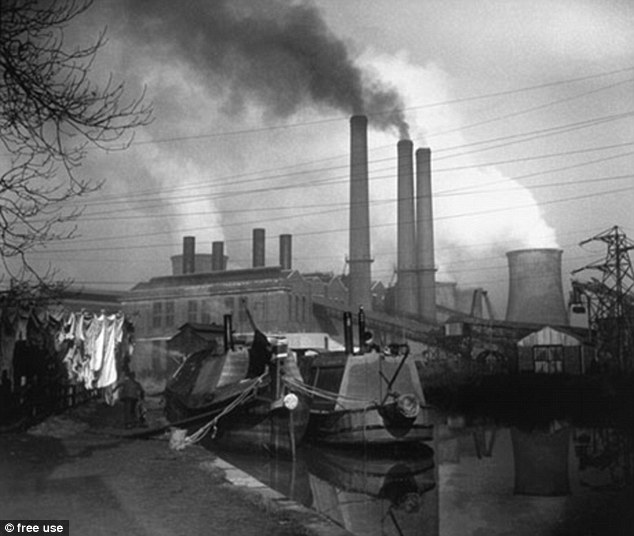

All the boats on the canals were horse-drawn. Packet boats carrying packages weighing up to 112 lbs (51 kg) as well as passengers at relatively fast speeds day and night were introduced onto the canals. To compete with the expanding railways, the flyboat was introduced, cargo carrying boats working day and night. These boats carried three men who operated a watch system. Two crewed while the other slept. Horses were changed regularly.

When steam boats were introduced in the late nineteenth century, crews were enlarged to four. The boats were operated by individual carriers, or by carrying companies who would pay the captain a wage depending on the distance travelled, and the amount of cargo.

CANAL PEOPLE

During this period, whole families lived aboard the boats.

They were often marginalised from land-based society. This became standard practice across the canal system, with in many cases families with several children living in tiny boat cabins 10 feet by 6 feet (3 m by 1.8 m), creating a considerable community of boat people. Life was hard with children born in the cabin.

Babies often slept in a drawer beneath their parent’s bed. The boatman’s cabin was wonderfully designed to maximise cupboard space with fold down table and bed. A coal stove range occupied the corner of the cabin giving heat and was used for cooking meals. The cabins were beautifully decorated usually with roses and castles and adorned with china plates and highly polished brassware. Though this community had much in common with gypsies both communities strongly resisted any such comparison, and surviving boat people feel deeply insulted if described as “water gypsies”

RAILWAY COMPETITION

From about 1840 railways started to threaten the canals as they could carry more freight and transport goods and people far more quickly than the walking pace of the canal boat. Most of the investment that had previously gone into canal building was diverted into railway building.

The canal companies were unable to compete and in order to survive they had to cut their prices. This reduced the previously earned huge profits and impacted on the boatmen’s wages. Flyboat working virtually ceased as it could not compete with the railways on speed.

By the 1850s the railway system had become well established and the amount of cargo carried on the canals had fallen by nearly two-thirds. In many cases struggling canal companies were bought out by railway companies. Sometimes this was a tactical move to gain ground in their competitor’s territory, but sometimes canal companies were bought out, either to close them down and remove competition or to build a railway on the line of the canal. The larger canal companies were able to survive and make profit. The canals survived through the nineteenth century largely by occupying niche markets that the railways had missed, or by supplying local markets such as the coal-hungry factories and mills of the big cities. Overall the canals adapted to the appearance of the railways and in 1900 the canal network differed little from its extent in 1830.

NATIONALISATION

The canal network gradually declined, and during the 1920s and 1930s many canals, mostly in rural areas, were abandoned due to falling traffic, caused mainly by competition from road transport. However, the main network saw brief surges in use during the First and Second World Wars carrying raw materials and munitions for the war effort. They still carried a substantial amount of freight until the early 1950s.

Most of the canal system and inland waterways were nationalised in 1948, along with the railways, under the British Transport Commission. In 1955 the British Transport Commission placed the canals into three categories according to their economic prospects; waterways to be developed, waterways to be retained, and waterways having insufficient commercial prospects to justify their retention for navigation. The 1950s and 1960s saw a rapid decline in freight transport on the canals in the face of mass road transport. Most of the canal transport at this time was coal-carrying to waterside factories which had no other convenient access. Eventually during these decades these factories either switched to cleaner fuels or ceased trading.

In 1963 the canals were transferred to the British Waterways Board (BWB), then to become British Waterways (BW) and today the Canal And River Trust (CART). 1963 was an incredibly hard winter with boats frozen in their moorings and unable to move for weeks at a time. This was one of the reasons for BWB to formally cease most of its narrowboat carrying on the canals – with boats and traffics transferred to a private operator, Willow Wren Canal Transport services. By this time the canal network had shrunk to just 2000 miles, half the size it was at its peak in the early 19th century, however the basic network was still intact.

TRANSPORT ACT 1968

The Transport Act 1968 classified the nationalised waterways as:

Commercial – waterways that could still support commercial traffic

Cruising – waterways that had a potential for leisure use, such as cruising, fishing and recreational use

Remainder – waterways for which no potential commercial or leisure use could be seen

BWB was required, under the Act, to keep Commercial Waterways fit for commercial use; and Cruising Waterways fit for Cruising. There was no requirement to maintain Remainder Waterways or keep them navigable.

RESTORATION

Though commercial use of the canals declined after World War II, recreational use gradually increased as people had more time and disposable income. The establishment in 1946 of a group called the Inland Waterways Association has helped revive interest in the canals to the point where they are a major leisure destination.

Many restoration projects have been led by local canal societies or trusts, who were initially formed to fight the closure of a remainder waterway or to save an abandoned canal from further decay. They now work with local authorities and landowners to develop restoration plans and secure funding.

SALTISFORD CANAL TRUST

The Warwick and Birmingham Canal carried freight to Warwick Bar in central Birmingham – then the heart of the Industrial Revolution in the “city of a thousand trades” –constructed by the surveyor Samuel Bull and the engineer William Felkin, following an Act of Parliament in 1793.

Technically the canal had to overcome the difficulties of descending from the plateau that Birmingham is built on down to the Leam-Avon valley containing Warwick. The main source of water was Olton reservoir, but in 1796 a Boulton and Watt stem engine started work in Bowyer Street, Bordesley, to pump water from the bottom to the top of Camp Hill locks. Major features on its 22 mile length included lock flights at Camp Hill and Knowle, a 433 yard tunnel through sandstone at Shrewley and a major lock flight of 21 locks at Hatton, until terminating at the important garrison county town of Warwick, serviced by the Saltisford Wharf.

Early supporters of the new canal included the Earl of Warwick and the Birmingham Canal Navigations Company – for whom it provided a route to the south.

The canal officially opened in 1799 and joined with another new canal the Warwick and Napton. This opened a direct route to London and was part of the grand cross strategy to link the four major ports of England – London, Liverpool, Bristol and Hull.

Initially the canal was a success and joined with the Birmingham And Warwick Junction Canal in 1844, a short navigation built to relieve congestion at the Birmingham end. However, competition from the steam railways led to a two thirds drop in revenues and the two canals agreed to be sold to the London and Birmingham Railway for closure and conversion into railway lines for the large sum of over half a million pounds. The deal, however, fell through and the navigation stayed open.

In 1895 the Warwick and Birmingham and the Warwick and Napton canals merged to form the Grand Junction Canal Company. Falling freight volumes led in 1917 to the merging with the Warwick and Birmingham Junction Canal under one management, eventually known as the Grand Union Canal.

Over thirty years ago the historic Saltisford canal arm of the Grand Union Canal – which once served basins near what is now Sainsbury’s supermarket – lay derelict, unloved and in danger of being filled in.

In 1982 a group of volunteer enthusiasts stepped in and saved much of the arm – sadly some has been built on –and painstakingly restored it.

They set up the Saltisford Canal Trust – a registered charity – and its trading company subsidiary, Saltisford Canal Trading Ltd, which manages the site. The Trust has succeeded in its initial aim of saving and restoring the arm to navigation. It now owns the moorings which help provide some of the funds to enable the Trust’s activities:

Having a day hire boat Saltie II which has disabled access

Opening the grounds and gardens to the public

Safeguarding the navigation and promoting the use of the canal in Warwick

Promoting knowledge of the historic significance of the canal on Warwick’s development.

Providing moorings and services for visitor boats (over 1000 per annum) and long term moored narrowboats

A superb cedar clad meeting room for meeting hire and educational purposes

The Trust, which is governed by volunteers, receives no government grants. It is self-financing raising funds – via its trading company – from its moorings, day hire boat, canal shop/visitor centre, meeting room, charitable gifts and donations and membership.